Tomorrow night marks the beginning

of Passover. I am certain that most of

us will be keenly aware that this seder

will be the second time we hold our Seders during the Pandemic. Once again many of us are not able to join loved ones in person this year.

The year has taken a very heavy toll on us all. During the pandemic, 4 in 10

adults have reported symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, up from one in ten before the pandemic. There has been an

increase in the number of people reporting difficulty sleeping, focusing,

working, and learning. Consumption of

alcohol and other drugs as well as overeating

has increased. There has been an overall worsening of chronic

medical conditions due to the worry and

stress of the coronavirus and the social isolation as a result of it.

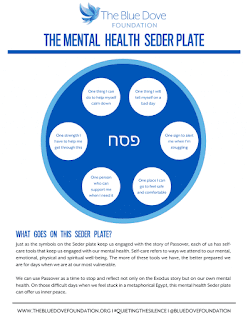

Therefore, I was intrigued when I

came across “The Mental Health Seder Plate”, an interpretation of the Seder

plate put out by the Blue Dove Foundation. The Blue Dove Foundation, based in

Atlanta, was created three years ago to help address the problems of mental

illness and addiction in the Jewish community and beyond.

For example, the Zeroah, or

shankbone on our seder plate, has traditionally represented the “outstretched

arm” through which G-d brought us out of Egypt. But it can be a reminder as

well that at different times in our lives we are all in need of “an outstretched

arm”. We need to remember that it is OK to accept help when it is offered to

us. When we are in a better place, we can then extend our own arms to help

others.

The egg on our seder plate

traditionally represents one of the sacrifices made in the Temple on Passover

during ancient times. They

highlighted an interesting thing

about the egg. The longer it is cooked, the harder it

gets! So too, we need not be weakened by the flames of adversity. We too can be

resilient. In our struggle to overcome, we can become even stronger.

The karpas, or parsley, represents

the Spring and birth and growth. However, we dip the parsley in salt water, the

symbol of tears. For us, it is a reminder that birth and growth are often

accompanied by struggle and pain. Giving birth certainly involves pain – and raising a family involves pain as

well. In fact, the traditional term in

Yiddish for raising children is “Tsaar Gidul Banim” – literally, “the sorrow of

raising children.” In order to experience the joys of parenthood, of seeing our

children grow, we must inevitably endure the sorrows as well.

We eat the bitter herbs to remind

us of the bitterness of slavery. This teaches us the importance of remembering

the bitter times in our lives, as well as the sweet. We should not simply

forget our personal struggles. Rather, there is a time and place to look at

them directly and remember them. We have much to learn from the hardships and

misfortunes in life.

The Charoset, of course, represents

the bricks and mortar that our ancestors used when they were slaves in Egypt.

It is also sweet to the taste. From a mental health point of view, the Charoset

represents the hard work that goes into building a productive life; the

sweetness the freedom that we can achieve from that very work. It is a reminder

that when we feel hemmed in by our life circumstances we can be active

participants in our own lives and work

change the things in our life that we do not like.

Despite our society becoming more

enlightened and compassionate about mental health issues, there is still much

we need to do. We often act as if anxiety, depression, addiction and other

reactions to the stresses of life are some kind of peculiar afflictions that

can be addressed by toughing it out, straightening ourselves up, putting our

mind to it, and hiding it from others. Let our seder plate be a reminder to us

that there is no shame in reaching out and getting help. That we can be strong

in the broken places. That growth often involves pain, but it can lead us out

of the narrow places we find ourselves, out of our own personal Egypt, and into

freedom.

Shabbat Shalom

![Chris Liverani [Unsplash.com]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiSMqHF59kp_zws7hc4xHmZZ6p-nYTDgOKl6TDzu5TGgz6QKqGim-DIASlZovq4wyTAeDkF0sj0PPPGbElakvtpUB-sAeW9CKBr4jjvIPYtCxNmPbGq4FOgxK2w4zYwXBJ2RGAELrnOGNei/w150-h200/errors.jpg)